Considering the effects of walking or running straight towards a dog

A reflection on head-on approaches from a dog body language perspective – a reason to curve off the path occasionally.

A simple body language experiment – Are there any differences between how a dog and human may approach one another?

I remember the period of my life when I used to commute from the suburbs into the city every day for work. It was a short walk to the station from my house; many times, I had to walk briskly down the road, or even jog (with wet hair) in order to catch the train on time. A dog lived at the corner house, opposite the station. Every morning and evening, the dog would stand behind his house gate and bark at the hasty commuters passing by.

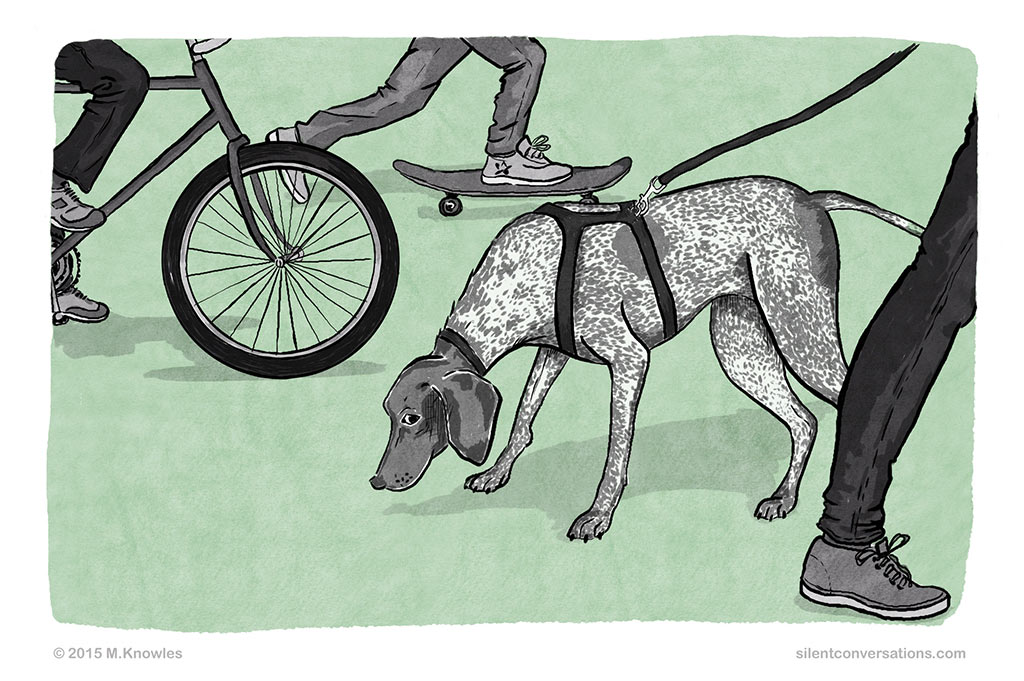

From a human perspective, walking straight down the pavement seems mundane, as though there is nothing to consider about the topic. We live in cities and towns where every day we walk straight down a pavement directly towards a flood of people. People jog past us, bicycles and skateboarders pass us; sometimes we are late and walk with haste, not noticing the world pass us by – these are humdrum, everyday occurrences in the human world and nothing unusual. If you see a dog ahead, have you ever considered the effect on the dog as you walk towards it and pass it on the pavement? How do things appear from the dog’s perspective? Are there any differences between how a dog and human may approach one another?

On one occasion, I had time to spare and was able to be carefree about getting to the station on time. I decided to try a body language experiment with the dog at the corner house. Seeing the dog ahead, ready and waiting to bark at me, I carried on walking calmly in a natural manner but slowed my pace. A little before I reached the garden wall of the house, I started to curve off the path a bit and turned my shoulder ever so slightly away from the dog. When passing the dog, I averted my gaze and turned my head away (I could still see the dog with my peripheral vision). No bark! I was overjoyed that the experiment worked and the small amount of courteous body language seemed to pay off in this instance. Some dogs may need even more space; every situation and dog is different, so what may be enough for one, may not be for another.

When dogs approach each other, they do not rush up, straight towards each other. This kind of behaviour may be typical of a puppy, adolescent or individual who has not honed the finer nuances of polite appropriate social greetings. Careful negotiation and communication start a distance away in dog communication. The dog may slow down, start curving, sniff the ground, assess how the other dog is responding to its body language, offer appropriate body language signals, and make a decision whether to approach (usually in a polite curve or subtle curving of the body), or it may choose to slowly meander away, choosing not to interact with this particular individual. It is also worth considering that dogs have a phenomenal sense of smell. I know my dog has picked up or followed a scent of a dog that is quite a distance away, so there is a possibility that information has been gathered from scent already at a distance.

Are head on approaches considered polite in dog body language terms?

My dog is not comfortable with other dogs and occasionally certain people. Because of this, I try to avoid or offer a bit more distance from dogs and some people on walks, to help him cope with the situation. Sometimes things don’t go to plan, but I try my best. In the case of a dog approaching, I will change direction or cross the road, depending on the situation and the space necessary to allow my dog to deal with the situation. I would avoid approaching another dog head-on with my dog. My choice of avoiding may seem odd or unfriendly to some people, but it actually is very polite and the friendly thing to do from a dog communication point of view. I have had a few occasions when people continue to walk directly at me with their dogs or even decide to follow me and cross the road to approach directly (though I have deliberately turned my back on them). I find this behaviour odd. In human culture, too, turning one’s back would be an obvious signal that you do not wish to interact. Based on the experiences they have had with their own dogs, people may feel they have friendly dogs and there is no need for avoiding, but they cannot be certain that the other dog has had the same experiences.

Even for “friendly” dogs, walking directly towards another dog is impolite and awkward from a dog communication perspective, and such behaviour may not actually be considered that friendly, especially from a strange dog that they have never met before. Sure, there are some dogs that seem to tolerate this, but there are many that struggle. Slight curving either of the body or approach, along with other body language signals would be more appropriate. There are also dogs who may need space (DINOS) and prefer no approach at all. Funnily enough, I have looked back at a person who was hot on my tail with a supposedly “friendly” dog. I could see their dog expressing the opposite emotion with its body language, showing that they would rather not approach, but the person was unaware of the subtle body language his dog was showing. It is also a strange expectation that a dog should meet with every strange dog that he bumps into on the street. We don’t walk up to strangers on the street and look to interact with every stranger, so why would we have that expectation for our dogs?

Dog walkers’ courtesy – consideration for on-lead dogs

It is also worth considering how it feels to be on a lead. Being on lead can make a dog feel trapped, as there is no escape or control over a situation. Imagine being tied to someone and relying on them to make all the choices! It really depends on the guardian’s skills and observations as to what situations the dog is placed in, so the dog is vulnerable to the guardian’s choices. It is advisable and courteous to avoid approaching another dog which is on-lead with your dog, unless you ask the guardian if you are allowed to approach and they give you permission to do so. I would especially not approach if the dog is on a short lead and unable to express its true feelings through body language, due to being restricted. Dogs use their entire body to communicate; if their movement is restricted with certain walking equipment, they may not be able to communicate fully. I would rather avoid an encounter if I cannot see the full capacity of communication occurring between dogs. It would also be unfair for an off-lead dog to approach an on-lead dog, as the on-lead dog has the disadvantage of no escape due to the lead and can feel threatened.

I am hoping it becomes common knowledge and courtesy between dog walkers not to allow the off-lead dog to approach an on-lead dog – it should be common dog walking etiquette. If you see a dog ahead, call your dog and put him on lead. Always communicate at distance with the other dog guardian. It is courteous to ask if you can approach with your dog, even if your dog is on-lead.

Going back to head-on approaches … How would you feel if a stranger ran towards you at full speed?

Would it make you feel uncomfortable? You would wonder what they wanted, what they were up to; it could seem quite threatening. What if they were wearing sneakers and lycra? I guess seeing it from that perspective, you would understand there is no threat – it is just a jogger out on a run. Dogs do not understand the association of lycra with exercise, and the fast movement directly towards them can seem scary and threatening.

From a dog’s perspective, a direct, speedy, front-on approach can be seen as threatening behaviour. Another dog might do this to threaten and intimidate, or they may be impolite with such an approach. If the other dog were trying to be polite, they would take their time and negotiate a slow approach and offer appropriate body language signals. Direct eye contact, staring and front-on body posture is also used to threaten and can be used as a warning to the other party.

So, seeing joggers, cyclists or skateboarders from a canine perspective might explain why there is such a reaction to them from dogs. If you are jogging or cycling and approaching a dog ahead, I would avoid racing directly past or towards it; this could frighten or threaten the dog, and there is a chance it might bite you out of fear. I thought this would be an appropriate opportunity to share Jessica Dolce‘s (creator of DINOS – Dogs In Need Of Space) humorous blog post, ‘How to Score a Dog Bite: The Joggers and Bikers Edition‘ as further reading.

The Dog Pulse project – measuring pulse rate of dogs with head on and curved approaches

Youtube video from the Dog pulse Project

There is an interesting project called the Dog Pulse Project where they measured the pulse rate of dogs with a person approaching the dog head-on in a straight line or approaching in a curve. The pulse rates of the dogs seemed to go up with the head-on approach as opposed to the curved one. Interesting project and gives some food for thought.

Observing body language – How comfortable is your dog feeling with an approach?

Sometimes dogs may choose to sniff the ground as there is a good scent, but in other instances it might be a calming signal showing they are no threat or displacement behaviour showing that they are not feeling comfortable – all depending on the circumstances. Observe the situations in which they start sniffing the ground. I have seen dogs slow down, stop and start sniffing, due to seeing something ahead that they might not feel comfortable with. It is worth observing, taking note and listening to your dog, trying to understand what they may be communicating.

My dog copes with passing certain people on walks on the street, but he may not cope with others. The people that he struggles with are generally men – particularly those wearing hats and sunglasses. He is also wary of people who move very stiffly (front on, stiff, staring approach), and unusual looking or loud, animated people. I watch my dog’s body language carefully; he is able to move freely and express his body language on a harness and loose lead. I observe his interest level; he may start looking a bit taller, his movements become slightly more jittery, his ears go up and forward, and his tail might start pushing forward. Generally his tail is up and curled over his back, so there is a very subtle difference, with the tail moving slightly more forward or up at the base. In the case of other dogs who normally carry their tails at the same level as their backs, the tail base change in height is more noticeable than it is in the case of a tail that is curled over the back.

The other body language that my dog may display to communicate that he is not feeling comfortable with the person ahead is that he slows down and starts sniffing the ground. If he is not feeling at ease at a substantial distance, it is likely that he will not feel more comfortable as we move closer, so I prefer to find another route and avoid the person ahead. I have seen many dogs that are not able to express their discomfort, as they are on a short lead, unable to even touch the ground with their noses and express natural body language signals like sniffing or curving. I have also seen dog handlers not realizing that their dog is communicating discomfort via body language signals. The dog handler gets frustrated, thinking their dog is acting stubbornly or disobediently by slowing down, stopping and sniffing the ground, when he is actually trying to communicate rather than being stubborn. It is important that the dog is able to express himself and his body language is listened to. Even if I pass people that my dog is able to cope with, I try to curve a bit and provide a barrier with my body to make my dog feel more comfortable when passing.

There is some fantastic footage demonstrating a dog’s discomfort with regards to a person running straight up to the dog on Turid Rugaas’ DVD ‘The Wee Signs of Dogs‘. If you forward to 33:19 in the video, a woman runs straight towards a dog. The dog shows some wonderful body language by first turning his head then his whole body away in response to this approach. Shortly afterwards, the dog shows some displacement behaviour by rolling on the ground, revealing how uncomfortable he felt with this direct fast approach. Displacement behaviour like biting the lead, biting clothing, humping, scratching or rolling can occur if the dog is put in situations that are too much for him. The behaviour indicates that he may not be coping, so it is worth observing your dog’s body language carefully to understand when he many need more support from you. The dog in the video was on a loose lead and able to show his discomfort through his body language. There are many dogs placed in situations they cannot cope with, that require them to ‘sit’ or ‘stay’ without allowing them to express their true feelings about the situation with body language or the choice to remove themselves. Giving dogs some choices by allowing them to avoid situations that they don’t have the skills to cope with is a much less stressful option for them.

There is some fantastic footage demonstrating a dog’s discomfort with regards to a person running straight up to the dog on Turid Rugaas’ DVD ‘The Wee Signs of Dogs‘. If you forward to 33:19 in the video, a woman runs straight towards a dog. The dog shows some wonderful body language by first turning his head then his whole body away in response to this approach. Shortly afterwards, the dog shows some displacement behaviour by rolling on the ground, revealing how uncomfortable he felt with this direct fast approach. Displacement behaviour like biting the lead, biting clothing, humping, scratching or rolling can occur if the dog is put in situations that are too much for him. The behaviour indicates that he may not be coping, so it is worth observing your dog’s body language carefully to understand when he many need more support from you. The dog in the video was on a loose lead and able to show his discomfort through his body language. There are many dogs placed in situations they cannot cope with, that require them to ‘sit’ or ‘stay’ without allowing them to express their true feelings about the situation with body language or the choice to remove themselves. Giving dogs some choices by allowing them to avoid situations that they don’t have the skills to cope with is a much less stressful option for them.

Final round up – the dog’s perspective and human expectations

I hope this provides some understanding to the joggers, cyclists and skateboarders as to why dogs may react to them. Pavements may be straight, and our human perspective is to follow straight paths, but it is worth curving (even if it is very subtle) and going off the path occasionally, especially if you see a dog ahead. For dog guardians, observing the body language of the dog and providing support where needed may mean avoiding a particular environment or situation in some instances. Consider, too, how much pressure is placed on the dog to conform to human expectations. There are some great dogs that seem to tolerate these demands, but even with great dogs, it would be a friendly gesture to curve off the path. In the case of dogs that struggle to cope, I hope this provides some understanding on seeing matters from their perspective. For these dogs, streets can be a difficult environment to navigate. Your dog is not misbehaving; he is just being a dog and may need more support to cope with a human world and human perspective. Perhaps a quieter environment may be more appropriate. If you see a dog reacting, barking or lunging, please give them lots of space; do not continue to approach: cross the road, and curve away – a friendly gesture that will be appreciated by the dog and guardian.

Video footage of subtle dog body language

I will leave you with a short subtle video showing a dog curving on approach. At first you may watch it and think there is nothing going on, but if you watch it again, you will see the dog subtly curving to the right on approaching the person. You will also see some polite body language on approach; at 0:05 there is a head dip and head turn. At 0:10 you can see the dog’s body starting to curve very slightly as she starts to curve to the right on approach – another quick head turn. At 0:11 another head dip; the eyes are soft, slightly shortened and almond shaped. There is a soft gentle tail wag on approach. With the slight curve, this means the side of the dog’s shoulder is facing the person on approach rather than the front of her body. It is worth also noting the speed and pace in which she approaches.

Video Credit: Lisa Kanne from One on One Dog Training

Martha Knowles

Author

My vision is to create a community of dog guardians who share their observations and interpretations of their dogs’ silent conversations. Hopefully, these experiences and stories will provide some insight into dog communication, which is often overlooked by the untrained eye because it is unfamiliar to humans. We are accustomed to communicating mainly with sound, so we are not attuned to the silent subtle gestures and body language used by dogs to communicate. If you take the time to observe, you will start to see these 'silent conversations' going on around you. My dream is for dog communication to become common knowledge with all dog guardians and as many people as possible. Surprisingly, there are still some professionals working in various dog-related careers who are uneducated about dog body language. Greater awareness of how dogs communicate will help to provide better understanding and improve the mutual relationship between dogs and humans. This will promote safer interactions between our two species and hopefully remove some of the expectations placed on dogs within human society. I would like dog guardians to feel empowered with their knowledge of dog communication so that they can be their dogs’ advocates and stand up for themselves and their dogs when it really matters.